On June 1, 2022, the New York State Senate passed Bill No. S08892 in a 63-0 vote, which the New York State Assembly passed on May 3, 2022 in a 147/0 vote (Bill No. A04601). This law adds a new requirement for principals of a power of attorney who are trustees or beneficiaries to put co-trustees and co-beneficiaries on notice that they signed a power of attorney. While the law has a commendable purpose—"To provide more transparency in certain financial matters."—it has serious problems and should not be passed into law by Governor Hochul.

Proposed Statute

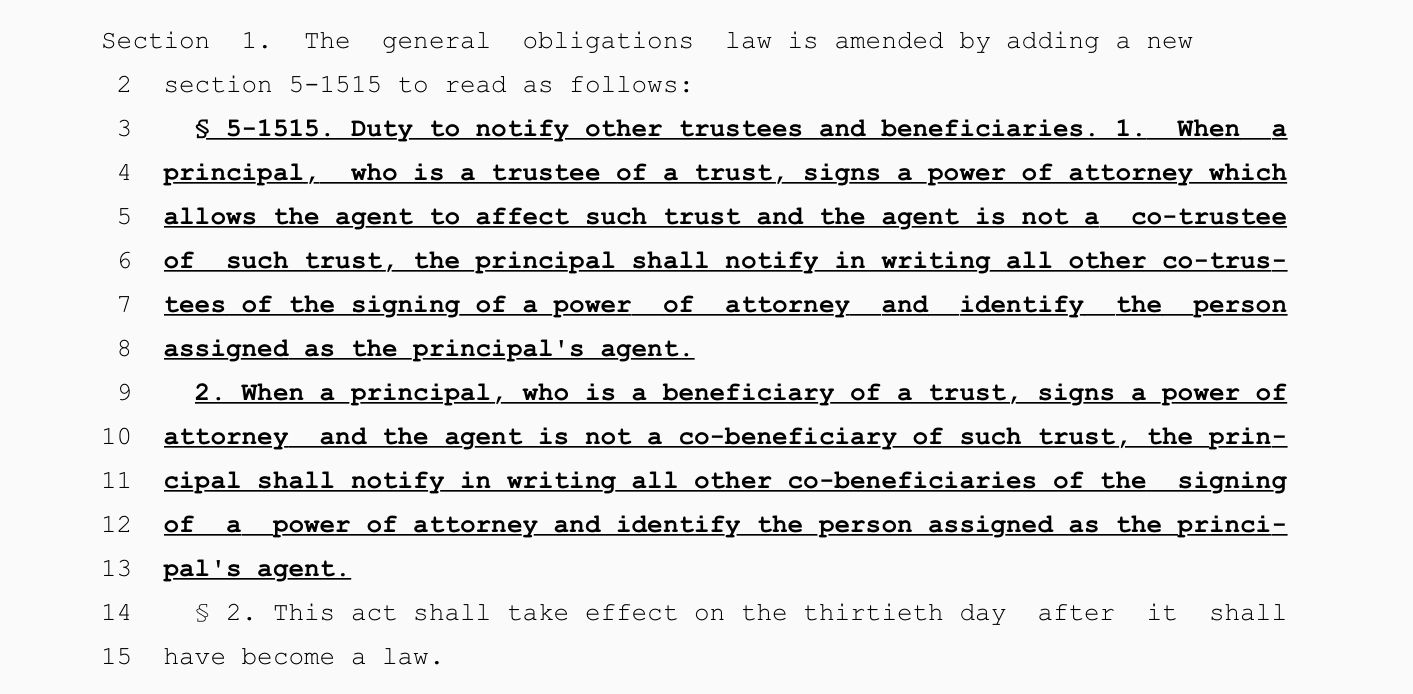

Bill numbers A04601 and S08892 are the same. They propose to add a new section to the New York's General Obligations Law: "§ 5-1515. Duty to notify other trustees and beneficiaries." Here is the proposed law:

Proposed GOL § 5-1515 imposes a duty on certain principals. A "principal" is the individual who signs a power of attorney and designates someone else (the "agent" or "attorney-in-fact") to act on the principal's behalf. GOL § 5-1501(2)(k) defines “principal” as "an individual who is eighteen years of age or older, acting for himself or herself and not as a fiduciary or as an official of any legal, governmental or commercial entity, who executes a power of attorney." GOL § 5-1501(2)(a) defines “agent” as "a person granted authority to act as attorney-in-fact for the principal under a power of attorney, and includes the original agent and any co-agent or successor agent."

Proposed GOL § 5-1515(1) imposes a duty of notice on (1) a trustee (2) of a trust that has at least one other trustee (a "co-trustee") (3) who signs a New York power of attorney (i.e., the trustee becomes a principal) (4) that empowers the agent of the power of attorney to act on behalf of the principal as trustee or change the trust ("to affect such trust") (5) and that agent is not a co-trustee. So, "A" and "B" are co-trustees, and "A" signs a power of attorney naming "C" as the agent and empowering the agent to act on behalf of "A" with respect to the trust. This individual, the trustee/principal ("A"), would have to give the other co-trustees ("B") a written notice, which states that "A" signed a power of attorney and that "C" can act on behalf of "A" to "affect" the trust.

Proposed GOL § 5-1515(2) imposes a duty of notice on a beneficiary of a trust who signs a power of attorney that names someone other than a "co-beneficiary" as the agent. So, "A" and "B" are "co-beneficiaries" of a trust, and "A" signs a power of attorney naming "C" as the agent. The co-beneficiary/principal ("A") must give “B” a written notice, which states that "A" signed a power of attorney and that "C" can act on behalf of "A."

Rationale for the Proposed Law

The rationale for the bill is articulated in the "Justifications" section of the Memorandum in Support of Legislation:

This bill will protect trustees and/or beneficiaries in particular financial matters where said trustee/beneficiary is a co-trustee and/or co-beneficiary. In instances where you share an account/trust/etc. with another trustee and/or beneficiary, the other trustee/beneficiary could create a power of attorney with a non-party. Without any notice, that non-party could then perhaps raid the trust or financial agreement, thus taking all funds. This bill would require notice to all trustees and/or beneficiaries when one member of the financial agreement enters into a power of attorney.

Problems with the Proposed Law

Several lawyers commented on the New York State Bar Association Trusts and Estates Law Section listserv that the proposed law has significant problems.

Problems with Proposed GOL § 5-1515(1)

(Problem 1) Proposed GOL § 5-1515(1) seems to implicitly permit the ability of trustees to delegate their duties using a general power of attorney. Addressing such a contentious issue should be made explicitly.

Proposed GOL § 5-1515(1) ignited a debate on New York State Bar Association Trusts and Estates Law Section listserv over whether a fiduciary can delegate duties by using a general power of attorney:

- Some attorneys think that a fiduciary cannot delegate duties at all under a general power of attorney. They assert that proposed GOL § 5-1515(1) tacitly condones what is not permissible in the law to begin with.

- Others think that a fiduciary cannot delegate duties under a general power of attorney to anyone other than a co-fiduciary, if the document permits such delegation.

- Some think that a fiduciary can and should be able to delegate ministerial duties. One lawyer gave this example: A trustee signs a contract to sell a residence, but uses a limited power of attorney and authorizes the agent to sign documents to effectuate the trustee’s power to sell the residence. In this example, the lawyer mentioned, no duty is being delegated.

The problem is that the law is not clear with respect to a fiduciary’s ability to delegate duties using a power of attorney.

For example, in Burton v. PNC Bank, 12 A.D. 3d 264, 784 N.Y.S.2d 544 (1st Dep't 2004), the First Department of the Appellate division allowed a trustee to delegate duties to a third party and dismissed the complaint by the co-trustee. But GOL § 5-1515(1) would not cover the facts in Burton because the power of attorney in this case appears to have been in place before the trust was established. Yet, GOL § 5-1515(1) would silently bless the result by implying that trustees can delegate their fiduciary powers by using a general power of attorney.

In contrast to Burton, in Matter of Jones, 1 Misc. 3d 688, 765 N.Y.S.2d 756 (Sur. Ct. Broome County 2003), the Surrogate’s Court refused to record a power of attorney in which one executor wanted to delegate duties to a co-executor. The Court stated, "A fiduciary cannot delegate the whole responsibility for the administration of the estate, even to a cofiduciary." GOL § 5-1515(1) would also not apply in this context because it contemplates only a principal-trustee, not other fiduciaries. Instead of providing any clarity on a fiduciary’s duty to delegate, GOL § 5-1515(1) only muddies things by suggesting that one fiduciary (a trustee) can delegate duties using a general power of attorney, while not addressing other fiduciaries.

(Problem 2) The statute does not state the consequences of failing to notify a co-trustee or co-beneficiary. Does the failure to put them on notice make the power of attorney a non-statutory power of attorney? What teeth does the requirement have? What is the penalty for non-compliance?

(Problem 3) Clients who use a lawyer might blame the attorney for failing to advise them of the notice requirement. The exposure that attorneys have will probably depend on the consequences of violating the statute.

(Problem 4) A principal who signs a power of attorney without the assistance of an attorney to advise them of their duties might not know about the duty to put a co-trustee or co-beneficiary on notice. As a result, unrepresented principals are likely to have compliance issues.

Problems with Proposed GOL § 5-1505(2)

The beneficiary notice section applies whenever a beneficiary of a trust chooses an attorney-in-fact who is not a beneficiary. It is not clear how requiring a beneficiary to notify "co-beneficiaries" does anything to protect anyone's interests.

(1) Beneficiaries do not have the right or ability to use a trust account as their own, so it is not clear how they can "raid the trust . . . thus taking all funds." In a discretionary trust, beneficiaries do not have the authority to draw down the corpus of the trust. In a mandatory trust, beneficiaries merely have the right to request income and corpus distributions according to the distribution schedule in the trust.

(2) If a beneficiary makes a ministerial power of attorney appointment, notice must be given to all the other beneficiaries. This serves no useful purpose.

(3) Just like the section with co-trustees, proposed GOL § 5-1515(2) has no teeth. What is the penalty for non-compliance?

(4) Even with the notice requirement that is proposed under GOL § 5-1515(2), "co-beneficiaries" will still have no standing and no power to interfere with the agent's actions.

(5) In some trusts, such as a "quiet" trust, "co-beneficiaries" might not even be known. The principal may be unaware of being a beneficiary of a trust. So, it would be impossible to comply with proposed GOL § 5-1515(2).

A Better Alternative?

The justification for GOL § 5-1515 is commendable. It strives to reduce the abuse of powers of attorney is specific situations. The execution of a power of attorney authorizes another party to act in one's place—with the agent as the alter ego of the principal. The Second Department of the Appellate Division described this authority as "extraordinary." Zaubler v. Picone, 100 AD2d 620, 621, 473 N.Y.S.2d 580 (2d Dep't 1984).

Proposed GOL § 5-1515(2) seems to serve no useful purpose.

In contrast, GOL § 5-515(1) strikes at a nerve. But before lawmakers address notice requirements, they must remove ambiguity and clarify the law by answering these contentious questions: (1) Can a fiduciary delegate the fiduciary's duties using a general power of attorney? (2) If the answer is yes, then are there limits on the ability to delegate duties?

After lawmakers settle the debate, they can revise GOL § 5-1515(1) so it is clearer and has some substance. Some suggestions: (1) Lawmakers should clarify what it means to "affect such trust." (2) More importantly, the law should state the consequences of failing to put a co-trustee on notice.

Hani Sarji

New York lawyer who cares about people, is fascinated by technology, and is writing his next book, Estate of Confusion: New York.

Leave a Comment