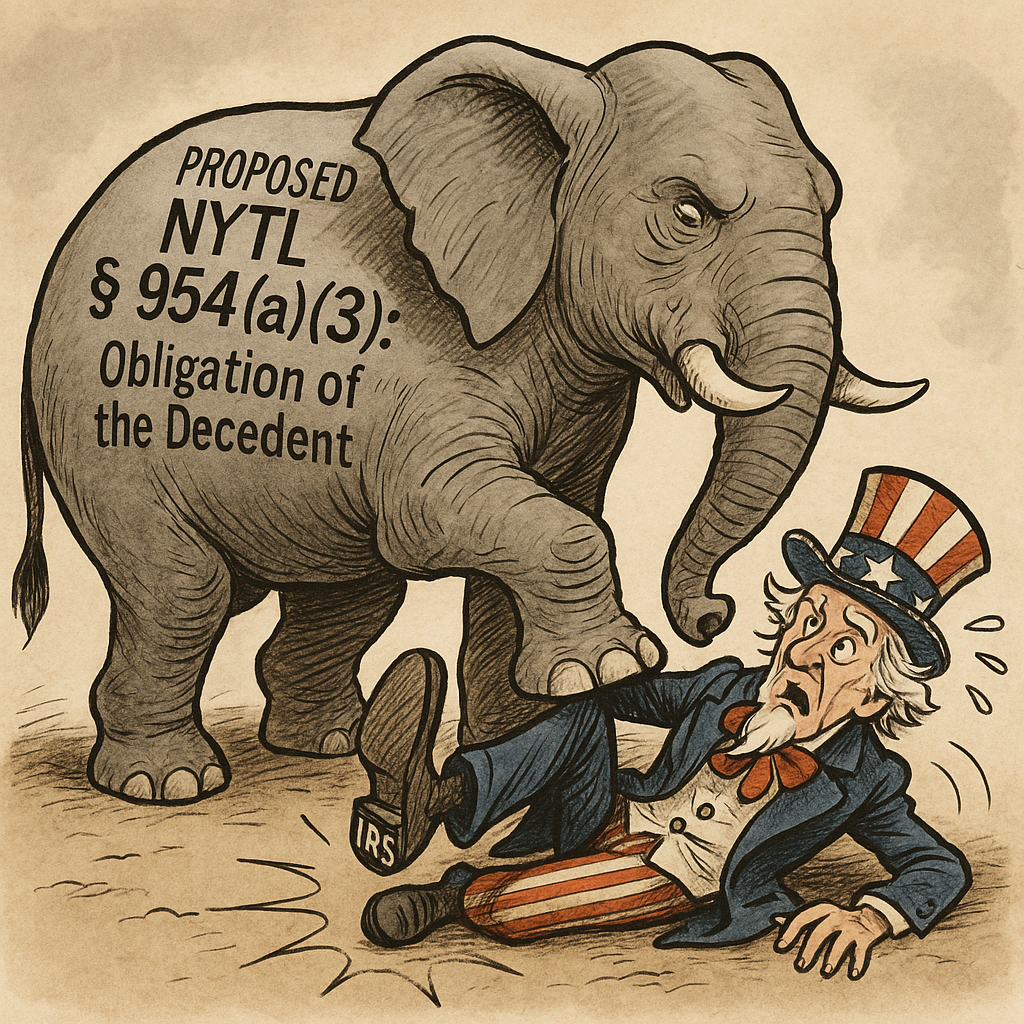

New York’s proposed amendment to Tax Law § 954(a)(3), included as Part T in the State Senate’s One-House Budget Bill (S.3009-B), tries something bold: It seeks to recharacterize part of the state estate tax as a deductible debt. Specifically, the proposal would deem the portion of the estate tax attributable to lifetime gifts made within three years of death—the so-called "clawback tax"—to be an "obligation of the decedent." The goal is straightforward: Maximize federal deductions for New York estates. But will the IRS go along with it?

This post explains why New York's attempt to secure federal deductibility for its recharacterized tax is doubtful:

- Substance over form: Calling a tax a "debt" doesn't change its true nature.

- Federal regulations narrowly define what qualifies as a deductible debt under IRC § 2053.

- As a hybrid tax/debt statute, the proposed NYTL § 954(a)(3) may raise an unsettled question of state law—shifting the analysis from Erie to Bosch, and allowing the IRS to interpret New York law rather than simply apply it as written.

- The SALT deduction saga shows that statutory recharacterizations—like calling tax payments "charitable contributions"—don't guarantee federal deductibility.

Proponents of the reform assert that the IRS must follow New York's statutory characterization. But a closer examination reveals that New York's reform may not work. The IRS may simply reject its attempt to make clawedback gifts deductible for federal estate tax purposes. Recent history shows that state statutes don’t control deductibility—federal law does.

Tax or Debt?

IRC § 2058 Permits a Deduction for Certain State Death Taxes

State death taxes are deductible under IRC § 2058, but this statute has a narrow deduction that excludes New York's clawback tax. IRC § 2058 permits a deduction for state death taxes only for property that is included in the decedent's federal gross estate.

IRC § 2058 states (emphasis added):

26 U.S. Code § 2058 - State death taxes

(a) Allowance of deduction.

For purposes of the tax imposed by section 2001, the value of the taxable estate shall be determined by deducting from the value of the gross estate the amount of any estate, inheritance, legacy, or succession taxes actually paid to any State or the District of Columbia, in respect of any property included in the gross estate (not including any such taxes paid with respect to the estate of a person other than the decedent).. . .

NY's Clawback Tax Is Not Deductible Under IRC § 2058

New York's clawback tax applies to gifts made within three years of death that are not included in the decedent's federal gross estate. New York Tax Law § 954(a)(3). So, the clawback tax is not deductible under IRC § 2058.

NYTL § 954(a)(3) states (emphasis added):

§ 954. Resident's New York gross estate.

(a) General.

The New York gross estate of a deceased resident means his or her federal gross estate as defined in the internal revenue code (whether or not a federal estate tax return is required to be filed) modified as follows:. . .

(3) Increased by the amount of any taxable gift under section 2503 of the internal revenue code not otherwise included in the decedent's federal gross estate, made during the three year period ending on the decedent's date of death, but not including any gift made: (A) when the decedent was not a resident of New York state; or (B) before April first, two thousand fourteen; or (C) between January first, two thousand nineteen and January fifteenth, two thousand nineteen; or (D) that is real or tangible personal property having an actual situs outside New York state at the time the gift was made. Provided, however that this paragraph shall not apply to the estate of a decedent dying on or after January first, two thousand twenty-six.

The inability to deduct clawedback gifts was identified as a shortcoming of the clawback tax when New York introduced it in 2014. A 2014 memo from the New York City Bar explains that the inability to deduct New York's clawback tax makes New York less competitive than other states (emphasis added):

[W]e are concerned whether gifts added back into the New York taxable estate for New York estate tax purposes would be deductible state death taxes for federal estate tax purposes pursuant to IRC § 2058(a), which provides a deduction for state estate taxes "in respect of any property included in the [federal] gross estate". This actually would make New York even more uncompetitive than it currently is compared to other states and increases, rather than decreases, the incentive for the very wealthy to emigrate. . . .

S.3009-B attempts to shift New York's clawback tax from being a non-deductible tax under IRC § 2058 to being a deductible debt under IRC § 2053.[1]

IRC § 2053 Permits a Deduction for Certain Debts

IRC § 2053(a)(3) provides a federal estate tax deduction "for claims against an estate."

IRC § 2053 states (emphasis added):

26 U.S. Code § 2053 - Expenses, indebtedness, and taxes

(a) General rule.

For purposes of the tax imposed by section 2001, the value of the taxable estate shall be determined by deducting from the value of the gross estate such amounts—. . .

(3) for claims against the estate, and

. . .

as are allowable by the laws of the jurisdiction, whether within or without the United States, under which the estate is being administered.

NY Proposal Attempts to Label Clawback Tax a Debt for Federal Estate Tax Purposes

S.3009-B has language that recharacterizes the clawback tax as an "obligation of the decedent," attempting to make the tax deductible for federal estate tax purposes under IRC § 2053.

S.3009-B states:

PART T

Section 1. Paragraph 3 of subsection (a) of section 954 of the tax law, as amended by section 1 of part F of chapter 59 of the laws of 2019, is amended to read as follows:

(3) Increased by the amount of any taxable gift under section 2503 of the internal revenue code not otherwise included in the decedent's federal gross estate, made during the three-year period ending on the decedent's date of death, but not including any gift made: (A) when the decedent was not a resident of New York state; or (B) before April first, two thousand fourteen; or (C) between January first, two thousand nineteen and January fifteenth, two thousand nineteen; or (D) that is real or tangible personal property having an actual situs outside New York state at the time the gift was made. Provided, however, that this paragraph shall not apply to the estate of a decedent dying on or after January first, two thousand twenty-six. The amount by which the total tax imposed under this article exceeds the total tax that would have been imposed under this article if this paragraph did not apply shall be treated as an obligation of the decedent as of the decedent’s death that is subject to the provisions of this article (but which shall not be deductible for purposes of this article).

§ 2. This act shall take effect immediately.

Do Labels Really Matter?

The question is whether New York's relabeling of the clawback tax as a debt will allow IRC § 2053 to control its deductibility rather than IRC § 2058.

In a private email exchange, the esteemed Jonathan Blattmachr, Principal at Pioneer Wealth Partners, questioned whether the clawback tax recharacterization can succeed under federal law. He wrote that “under Section 2053(c)(1)(B) inheritance, estate and similar taxes are not deductible under Section 2053. And it doesn't seem to matter whether it's an obligation of the decedent, the decedent's estate or an inheritor.”[2] Blattmachr added that he is working on an alternative that might work.

I’m grateful to Blattmachr for raising this issue. I had initially assumed (perhaps too optimistically) that the recharacterization could secure federal deductibility, but his comment prompted me to revisit that assumption.

My research confirms Blattmachr's concern: The regulations under IRC § 2053 suggest that labels alone may not control deductibility. The question might turn on whether the liability arises under a state’s estate administration law rather than its tax law.

Estate Taxes Are Not Deductible Under IRC § 2053

IRC § 2053(c)(1) explicitly prohibits a deduction under IRC § 2053 for state death taxes. This limitation makes sense because IRC § 2058 governs whether state estate taxes are deductible.

IRC § 2053(c)(1) states (emphasis added):

26 U.S. Code § 2053 - Expenses, indebtedness, and taxes

. . .

(c) Limitations

(1) Limitations Applicable to Subsections (A) and (B)

. . .

(B) Certain taxes.

Any income taxes on income received after the death of the decedent, or property taxes not accrued before his death, or any estate, succession, legacy, or inheritance taxes, shall not be deductible under this section.. . .

By its proposed recharacterization of an estate tax as a debt, New York is attempting to make the tax deductible under IRC § 2053(a)(3) and sidestep the limitation in IRC § 2053(c)(1)(B), which expressly prohibits inheritance, estate, and similar taxes from being deductible under IRC § 2503. But regulations under IRC § 2053 might undermine New York's debt label.

Merely Amending NY Tax Law May Cross Regulatory Line

Even if New York calls the clawback tax a “debt,” the IRS will examine where that obligation arises in state law. If the liability is rooted in tax law, rather than estate administration law, it may be disqualified from deduction under Treasury Regulation § 20.2053-1(b)(2)(iii). This regulatory boundary poses a serious hurdle to New York’s proposal.

Reg. § 20.2053-1(b)(2)(iii) adds a crucial limitation on what counts as a deductible debt. It states (emphasis added):

(a) General rule.

In determining the taxable estate of a decedent who was a citizen or resident of the United States at death, there are allowed as deductions under section 2053(a) and (b) amounts falling within the following two categories (subject to the limitations contained in this section and in §§ 20.2053-2 through 20.2053-10)—(1) First category.

Amounts which are payable out of property subject to claims and which are allowable by the law of the jurisdiction, whether within or without the United States, under which the estate is being administered for—. . .

(iii) Claims against the estate (including taxes to the extent set forth in § 20.2053-6 and charitable pledges to the extent set forth in § 20.2053-5); and

. . .

As used in this subparagraph, the phrase "allowable by the law of the jurisdiction" means allowable by the law governing the administration of decedents' estates. The phrase has no reference to amounts allowable as deductions under a law which imposes a State death tax.

Why This Matters: The regulation draws a sharp line between liabilities that arise under a state’s estate administration law and those imposed by its tax law. Only the former are potentially deductible under IRC § 2053.

The Problem with the Current Proposal: The clawback recharacterization appears in New York Tax Law § 954—part of the state’s estate tax code—not in the EPTL or SCPA, which govern the administration of estates.

As a result, the IRS may treat the liability as part of a state death tax, making it ineligible for deduction under § 2053. That distinction could be fatal.

Despite the new label, the clawback tax/liability remains an estate tax in substance:

- Clawbacked gifts are added to the New York gross estate under NYTL § 954(a)(3).

- The total New York estate tax is calculated in the usual way, based on the federal gross estate, expanded by clawedback gifts.

- The portion attributable to the clawback is then relabeled as a “debt.”

- The bill then states that the deemed "debt" is not deductible for New York estate tax purposes.

In short, New York's move is risky because federal law applies a substance-over-form doctrine. Calling a tax a "debt" does not necessarily make it so. If the liability results from the state’s estate tax calculation, then it likely remains governed by IRC § 2058—not deductible under § 2053.

An Overlooked Alternative (Amending EPTL 13-1.3) Highlights the Overlooked Paradox

In 2019, the New York State Society of CPAs Estates and Trusts Committee Report suggested a legislative workaround that takes Reg. § 20.2053-1(b)(2)(iii) seriously. Instead of merely amending the tax law, it proposed amending EPTL 13-1.3—a statute that governs how debts and expenses are paid from estates.

The 2019 Report states (emphasis added):

This tax trap could potentially be corrected if the New York Legislature were to amend section 13-1.3 of the New York Estates, Powers, and Trusts Law to statutorily treat the estate tax attributable to the 3-year clawback as a debt allocable to the residuary estate that came into existence immediately prior to the decedent’s death, except as may be otherwise provided in the deed of gift, will, or other governing instrument. See Comm’r v. Estate of Bosch, 387 U.S. 456 (1967). The New York Tax Law could be amended to provide that such debt is not deductible for New York State estate tax purposes, so as to render it "revenue neutral" for New York.

Why That May Work Better: By creating the liability within estate administration law, the deemed "debt" might:

- Satisfy the federal regulation’s requirement that the liability arise under administration law, and

- Avoid being treated as a state death tax under IRC § 2058.

Highlighting the Underling Problem: On the surface, reforming EPTL 13-1.3 might stand a stronger chance of withstanding federal scrutiny. It avoids the trap that § 2053 sets for taxes masquerading as debts—and respects the regulatory line between estate tax law and estate administration law. But the 2019 Report's proposal also highlights the underlying problem. Just as S.3009-B, it would retain revenue neutrality for New York by amending New York's estate tax so the deduction would not be deductible for NY estate tax purposes. This raises the crucial question: How is "the obligation of the decedent" from the clawedback gifts a true debt if it is included in the New York estate tax under NYTL § 954 and not deducted as a debt for New York estate tax purposes? Neither the 2019 Report's proposals nor S.3009-B adequately resolve this paradox, leaving room for the IRS to question it.

Let's slow down to clearly show this point. S.3009-B adds a cryptic parenthetical that should now make more sense--"but which shall not be deductible for purposes of this article".

Here is the reform that S.3009-B proposes, with parenthetical underlined:

PART T

Section 1. Paragraph 3 of subsection (a) of section 954 of the tax law, as amended by section 1 of part F of chapter 59 of the laws of 2019, is amended to read as follows:

(3) Increased by the amount of any taxable gift under section 2503 of the internal revenue code not otherwise included in the decedent's federal gross estate, made during the three-year period ending on the decedent's date of death, but not including any gift made: (A) when the decedent was not a resident of New York state; or (B) before April first, two thousand fourteen; or (C) between January first, two thousand nineteen and January fifteenth, two thousand nineteen; or (D) that is real or tangible personal property having an actual situs outside New York state at the time the gift was made. Provided, however, that this paragraph shall not apply to the estate of a decedent dying on or after January first, two thousand twenty-six. The amount by which the total tax imposed under this article exceeds the total tax that would have been imposed under this article if this paragraph did not apply shall be treated as an obligation of the decedent as of the decedent’s death that is subject to the provisions of this article (but which shall not be deductible for purposes of this article).

§ 2. This act shall take effect immediately.

The 2019 report explains the otherwise inscrutable parenthetical: New York is trying to make its clawback a tax deductible under IRC § 2053 by deeming it an "obligation of the decedent" but disallowing a deduction for the deemed debt for purposes of the New York estate tax. New York is attempting to impose its will on the federal government!

These bullet points demonstrate what New York is attempting:

- Is NY's clawback tax included in the decedent's gross estate?

- Federal estate tax: No. Federal law does not claw back all lifetime gifts. When it does claw back gifts, it adds them to the federal gross estate. See IRC § 2035.

- New York estate tax: Yes. New York starts its definition of "gross estate" with the federal gross estate and expands it by adding clawed back gifts. See NYTL § 954(a)(3).

- Is NY's clawback tax deductible?

- Federal estate tax: No.

- Not deductible under IRC § 2058 since the clawedback gifts are not part of the decedent's federal gross estate.

- Not deductible under IRC § 2053 since it is a tax.

- New York estate tax: No. New York's estate tax is not deducted from New York's gross estate.

- Federal estate tax: No.

- Is NY's clawback tax deemed as an "obligation of the decedent" deductible?

- Federal estate tax: ?

- New York lawmakers hope the answer is yes because it would be considered a debt under IRC § 2053.

- Some legal scholars do not think the new label will make clawback tax deductible under IRC § 2053. See Reg. § 20.2053-1(b)(2)(iii).

- New York estate tax: No. To prevent decreasing New York's estate tax revenue, New York lawmakers explicitly carve out the clawback tax/deemed obligation of the decedent from being deductible for purposes of the New York estate tax.

- Federal estate tax: ?

The message is clear: New York wants to preserve its own estate tax revenue while reducing the federal estate tax burden on its residents. By recharacterizing a portion of its estate tax as a deductible debt, the state aims to make itself more attractive to high-net-worth individuals. But this move effectively shifts the tax burden from the state to the federal government. While framed as tax relief for New Yorkers, the strategy raises broader concerns about federal revenue and the limits of state influence over federal tax law.

The Hidden Cost: Residuary Estate Bears the Burden

Even if New York succeeds in recharacterizing the clawback tax—either through Tax Law § 954 or a new amendment to EPTL 13-1.3—both approaches share a common flaw: They shift the entire tax burden to the residuary estate, which is an inequitable result that law reformers in New York are ignoring.

While these proposals may address federal deductibility, they do so at the cost of fair apportionment. That result runs counter to EPTL 2-1.8, which seeks to allocate estate tax equitably among all beneficiaries. Recasting the clawback as a debt enforceable only against estate assets risks overburdening the residuary while shielding transferees of lifetime gifts—an inequitable outcome the apportionment statute was designed to prevent.

Because New York lawmakers are overlooking the inequity created by shifting the entire burden of the clawback tax to residuary beneficiaries and because S.3009-B makes this change silently, I intend to explore the apportionment problem more fully in a separate post.

Does Bosch Support or Weaken New York’s Recharacterization?

Supporters of New York's proposed reform of NYTL § 954(a)(3) argue that the IRS would be bound by the state’s statutory recharacterization under Commissioner v. Estate of Bosch, 387 U.S. 456 (1967). But that reads Bosch too broadly and overlooks the decision’s more nuanced holding.

To understand what Bosch does—and does not—require, we need to walk through the federal framework step-by-step.

1. If the Statute Is Clear, Then Erie Governs

Federal authorities must apply a clear state statute or a rule announced by the state's highest court. Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938). If New York explicitly recharacterizes the clawback tax as “an obligation of the decedent,” and the statute is not ambiguous, then federal courts and the IRS must treat that obligation as a debt as a matter of state law. Under Erie, they have no authority to reinterpret clear state law.

In Erie, the United States Supreme Court held that federal courts sitting in diversity must apply state law as "declared by [the state's] Legislature in a statute or by its highest court. . . ." 304 U.S. 64, 78 (1938).[3]

The rule from Erie has since been applied more broadly. In Commissioner v. Estate of Bosch, 387 U.S. 456 (1967), the Supreme Court extended the Erie principle to federal tax cases:

This is not a diversity case but the same principle [from Erie] may be applied for the same reasons, viz., the underlying substantive rule involved is based on state law and the State's highest court is the best authority on its own law.

The Erie principle applies only when there is a clear state statute or the highest court has spoken on an issue; it does not apply when questions of state law have yet to be decided authoritatively.

2. If State Law Is Unsettled, Then Bosch Applies

Bosch governs whenever state law is unsettled—whether because a statute is ambiguous, or because the issue hasn’t been authoritatively resolved by the state’s highest court.[4] In such cases, federal authorities are not bound by lower state court rulings. Instead, they must determine what they find to be the applicable state law, giving "proper regard" to relevant rulings from other state courts, including intermediate appellate courts. Id. If New York explicitly recharacterizes the clawback tax as "an obligation of the decedent," but the statute is ambiguous, then federal courts and the IRS may interpret the state law and determine that New York’s highest court would not view this as a true debt enforceable under estate administration law. Under Bosch, they have the authority to interpret ambiguous state law.

As Bosch explained:

It follows here then, that when the application of a federal statute is involved, the decision of a state trial court as to an underlying issue of state law should a fortiori not be controlling. . . . [T]he State's highest court is the best authority on its own law. If there be no decision by that court then federal authorities must apply what they find to be the state law after giving "proper regard" to relevant rulings of other courts of the State. In this respect, it may be said to be, in effect, sitting as a state court.

This means the IRS need not defer to how New York labels the liability in a statute—unless the state’s highest court has spoken or the issue is otherwise settled. Federal authorities must make their own determination of state law, giving “proper regard” to intermediate court decisions, trial rulings, administrative interpretations, and other persuasive sources—but they are not bound by any of them.

And this is where the problem lies. The proposed amendment to NYTL § 954(a)(3):

- Adds gifts to the gross estate (a tax concept).

- Then, it calls the resulting liability a debt (an administration concept).

- But it states that the deemed debt is not deductible for New York estate tax purposes.

Whether New York’s highest court would consider this a genuine debt enforceable under estate administration law is not resolved by the text of the statute. That invites a Bosch analysis--one that could lead the IRS to reject the recharacterization as inconsistent with New York's true estate law.

Possible Collection Problem: One rationale the IRS might adopt—if acting as a state court under Bosch—is that characterizing the clawback tax as a debt could limit the state's ability to collect the tax. For example, if a decedent made a deathbed gift of all their assets, the gifted property would be pulled back into the New York gross estate for tax purposes. But if the estate holds no assets, there would be nothing from which to satisfy the “debt.” By contrast, treating it as a tax might allow New York to pursue recovery from the transferees.

That tension exposes the Catch-22 at the heart of the recharacterization: The added-back gifts are either part of a state estate tax, which may be recoverable from donees, or they are part of a personal debt of the decedent, enforceable only against assets the decedent owned at death. But they cannot be both. And since estate tax liability arises only at death—not before—it is not a true debt under IRC § 2053. The fiction collapses, and the drama of the reform ends in the tragedy of a permanently misallocated tax burden—one that falls squarely on the residuary estate. It's an inequitable result that undermines the apportionment principles codified in EPTL 2-1.8.

3. But Either Way, Federal Law Controls Deductibility

Even if the IRS concludes that New York law deems the liability a valid debt, that only satisfies state law. Deductibility under IRC § 2053 is a matter of federal law.

The IRS may still deny the deduction if it finds:

- The liability resembles a state death tax governed by IRC § 2058, or

- The obligation is not "bona fide" or "necessary to the administration of the estate" under federal standards.

So, while Bosch might allow New York to define the liability as a "debt" under state law, it does not guarantee that the IRS will accept it as a deductible debt under federal law.

This isn’t the first time New York has tried to reframe federal tax obligations. Recent history shows how federal authorities simply rejected states' efforts to manipulate federal tax law.

SALT Workarounds Show Federal Law Prevails Over State Framing

New York’s clawback recharacterization resembles an earlier failed strategy: State efforts to sidestep the federal cap on SALT deductions.

States Tried to Recharacterize State Taxes as Charitable Gifts

After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 capped the SALT deduction at $10,000, New York and others set up state-run charitable funds. Taxpayers could “donate” to these funds in exchange for large state tax credits—hoping to deduct the full amount as a charitable gift on their federal returns under IRC § 170.

The IRS Said No—and the Courts Agreed

The IRS issued final regulations (T.D. 9864) requiring taxpayers to reduce their federal charitable deduction by the amount of any state credit received. The IRS treated the transaction as a disguised tax payment.

T.D. 9864 states (emphasis added):

In response to the new limitation under section 164(b)(6), some taxpayers are seeking to pursue tax planning strategies with the goal of avoiding or mitigating the limitation. . . . Moreover, since the enactment of the limitation under section 164(b)(6), states and local governments have created additional programs intended to work around the new limitation on the deduction of state and local taxes.

. . .

. . . the final regulations retain the general rule that if a taxpayer makes a payment or transfers property to or for the use of an entity described in section 170(c), and the taxpayer receives or expects to receive a state or local tax credit in return for such payment, the tax credit constitutes a return benefit to the taxpayer, or quid pro quo, reducing the taxpayer’s charitable contribution deduction.

. . . the final regulations retain the rule that a taxpayer generally is not required to reduce its charitable contribution deduction on account of its receipt of state or local tax deductions. However, the final regulations also retain the exception to this rule for excess state or local tax deductions. . . .

New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut challenged the final regulations in court—but lost. In New Jersey v. Mnuchin, No. 19 Civ. 6642 (PGG), 2024 WL 1328595 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 30, 2024), the court upheld the IRS regulations, holding that the agency reasonably concluded these programs were tax payments in disguise, not deductible charitable contributions:[5]

The Court concludes that it was reasonable for the IRS to find that 'the [state or local tax] credit constitutes a return benefit' from the state or municipality 'to the taxpayer,' 'or [a] quid pro quo ... reduc[ing] the taxpayer's charitable contribution deduction.' 2019 Final Rule, 84 Fed. Reg. at 27514.

. . .

The Court concludes that the 2019 Final Rule constitutes a reasonable interpretation of IRC § 170 and is supported by a reasoned explanation. The Rule therefore survives deferential review under Chevron.

. . .

The Court concludes that IRS's promulgation of the 2019 Final Rule was not arbitrary and capricious.

In the SALT workaround litigation, New York had a stronger claim to standing. It argued that the 2019 Final Rule caused a direct loss of revenue by discouraging taxpayers from donating to state-managed charitable funds. These funds were created under a New York statute and allowed the state to offer tax credits in exchange for donations—letting it retain a portion of the funds. The court agreed that New York had shown a concrete fiscal injury.

By contrast, New York's clawback debt theory lacks that statutory grounding and fiscal harm. Without a direct loss or a statute at issue, it’s unclear whether New York would even have standing to challenge an IRS determination that the clawback tax is not deductible.

What About Bosch?

Bosch wasn’t central to the SALT workaround litigation because the issue wasn’t unsettled state law—it was how federal law should treat a transaction structured under state law. The courts said that the IRS was not bound by state labels.

The IRS had already issued the 2019 Final Rule, requiring taxpayers to reduce their charitable deduction under IRC § 170 if they received a state tax credit in return. In New Jersey v. Mnuchin, the court upheld that rule as a reasonable interpretation of federal law. It didn’t matter that New York called the payments “donations” or that the program was enacted by statute. Federal deductibility turns on substance, not form—and not state classifications.

This distinction matters for the clawback. Even if New York successfully characterizes the liability as a “debt” under state law, federal authorities may reject the deduction under IRC § 2053. That determination rests on federal standards—including whether the liability is bona fide, enforceable, and distinguishable from a state death tax.

The Lesson for NY’s Clawback Debt

The takeaway is simple: A state can call a tax payment a “donation” or a “debt,” but federal law controls deductibility. The IRS and federal courts will look at substance, not labels.

What If the IRS Says No?

Here’s the real risk: Even if the IRS denies the deduction under IRC § 2053, New York may still retain the statute. That’s what happened with the SALT workaround. The IRS said no, but New York kept the law in place.

The same could happen with the clawback provision:

- The clawback would be permanent, and

- The full burden could fall on the residuary estate, without any offsetting federal deduction.

Conclusion

New York's proposal raises important questions about how far a state can go in recharacterizing tax liabilities to influence federal treatment.

- If the statute is clear, the IRS may have to accept it as state law—but that doesn’t mean it's deductible.

- If the statute is ambiguous, Bosch allows the IRS to independently interpret state law.

- Either way, federal law determines deductibility under IRC § 2053—and substance usually wins over form.

New York may enact the statute. But getting a federal deduction? That’s still very much in doubt.

In my earlier post--NY Budget Proposal Makes Clawback Tax Permanent, Pushes for Deductibility, and Ends Apportionment for Gifts--I explain that in addition to recharacterizing the tax as debt, the proposed changes to NYLT § 954(a)(3) also eliminate the sunset clause, making the clawback tax permanent; and quietly remove the tax from the apportionment framework, effectively shifting the entire burden to the residuary estate. ↩︎

Quoted with permission. ↩︎

Before Erie, courts applied the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 1 (1842), under which they would independently determine matters of "general" law but deferred to states for matters of "local" law. Erie rejected that approach, citing its inconsistency with the Constitution and its tendency to encourage forum-shopping. The decision marked a shift: When state law governs a substantive issue, federal courts must follow it. ↩︎

I’m grateful to Professor William P. LaPiana, Dean of Faculty at New York Law School and Director of Estate Planning Studies in its Graduate Tax Program, for helping me refine my understanding of Commissioner v. Estate of Bosch, particularly the distinction between statutory ambiguity and unsettled state law. Any remaining errors are, of course, my own. ↩︎

Chevron deference may no longer hold. Since the case, Chevron deference has been overturned by the Supreme Court (Loper Bright decision, 2024), meaning courts may no longer automatically defer to agency interpretations. But even without Chevron, the IRS may still prevail—especially where states appear to be dressing up taxes as charitable contributions or where a state relabels a its tax as a debt just so the state tax can be deductible for federal estate tax purposes. ↩︎

- NY Tax Law § 954

- Federal Estate Tax

- Gifts

- IRC 2053

- IRC 2058

- Jonathan Blattmachr

- Legislation

- NY Bills

- NY Budget

- NY EPTL 2-1.8

- NY EPTL 13-1.3

- NY Estate Tax

- William P. LaPiana

Hani Sarji

New York lawyer who cares about people, is fascinated by technology, and is writing his next book, Estate of Confusion: New York.

Leave a Comment