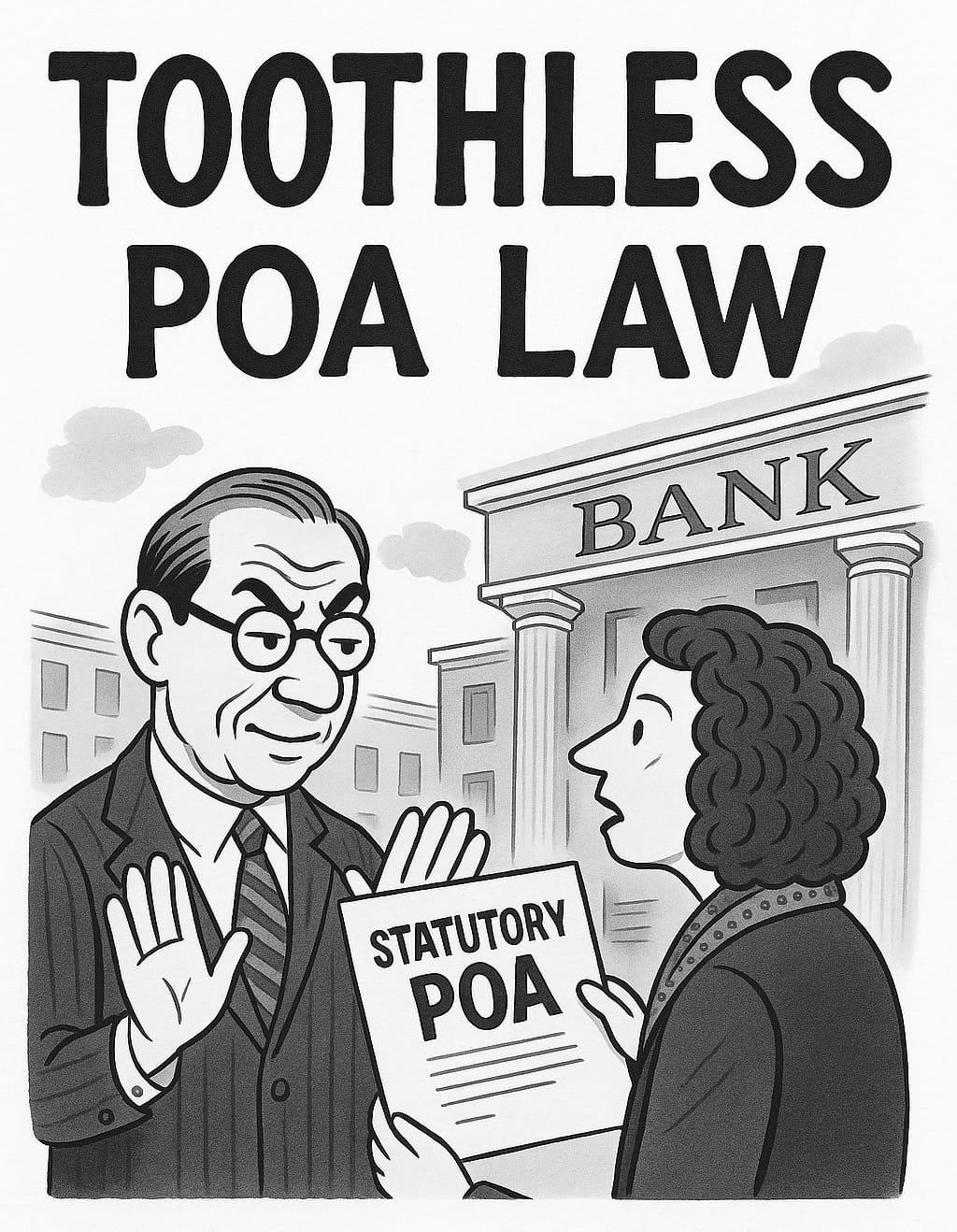

New York law requires banks and financial institutions to accept a valid statutory power of attorney (POA). That sounds strong on paper—but in practice, it's a law without teeth.

In this post, we’ll look at what the law actually says, how banks are ignoring it, and why the current enforcement mechanism fails the very people the law is supposed to protect. We’ll also explore how this gap in the law contributes to broader problems—like the misuse of joint accounts and unnecessary guardianship proceedings—and suggest a path forward that gives the statute real power.

What the Law Says

Under General Obligations Law § 5-1504, a bank or financial institution must accept a properly executed statutory short form POA unless it has “reasonable cause” to reject it. The law even sets a timeline:

- Within 10 business days, the institution must either:

- Accept the POA;

- Request an agent’s certification or attorney’s opinion of counsel; or

- Provide a written explanation for rejection.

The law also defines what qualifies as reasonable cause, such as suspicion of fraud or improper execution. And it includes a provision authorizing the agent to bring a special proceeding to compel acceptance.

What Actually Happens

In reality, banks continue to reject statutory POAs—often without justification. Why? Because there are no real penalties for refusal.

- The statute allows for a court order to enforce acceptance, but that’s a litigation burden placed on the person presenting the POA.

- The institution faces no meaningful consequence for dragging its feet or refusing outright.

- At that point, the individual is left to choose between initiating a lawsuit—or, in many cases, pursuing a guardianship proceeding, which may seem just as practical.

This creates an impossible choice for families trying to manage a loved one’s affairs. The law was designed to streamline access to financial accounts using a simple statutory form. But instead, it invites delay, confusion, and often litigation—precisely the outcomes the POA was meant to avoid.

A Legal Right Without a Remedy

The problem is not the form. It’s the lack of enforcement. When a bank refuses to honor a valid POA:

- It is breaking the law.

- But it faces no sanction.

- And the burden falls entirely on the person who needs access.

That’s not how legal compliance is supposed to work.

What the Law Requires—and What It Takes to Enforce It

Technically, New York provides a mechanism to enforce acceptance: a person can initiate a special proceeding under GOL § 5-1510 to compel a financial institution to honor a valid statutory POA. These proceedings are governed by CPLR Article 4, meaning they are designed as summary procedures—intended to be faster and more streamlined than full-blown litigation.

But in reality, they can still be burdensome. The agent or principal must prepare and file a petition, serve process, appear in court, and potentially engage in a contested hearing. And while courts can award damages and attorney’s fees for unreasonable refusals, the burden of initiating legal action still falls entirely on the individual.

This legal structure—an enforceable right with no automatic remedy—often deters enforcement. Many individuals find themselves choosing between costly litigation and initiating a guardianship proceeding instead. That trade-off undermines the very purpose of having a power of attorney in the first place.

The Policy Gap

The root cause of many joint account abuses, convenience account disputes, and guardianship petitions is the same: banks refusing to honor valid POAs.

If the Legislature is serious about fixing these problems, then it must confront this issue directly:

- Require banks to accept the statutory POA.

- Impose a penalty for noncompliance.

- Shift the burden off families and onto institutions.

Until that happens, families will continue turning to workaround strategies—like convenience accounts—that distort ownership, invite litigation, and create far more problems than they solve.

Hani Sarji

New York lawyer who cares about people, is fascinated by technology, and is writing his next book, Estate of Confusion: New York.

Leave a Comment